While teaching together at a local college in New York City, a colleague of mine would come to work every Monday morning with two bags of chocolate chip cookies. After distributing the contents of one bag to all of his associates on the faculty, he would knock on my door with the remaining bag of chocolate chip delights. He would then sit down in front of my desk, and we would proceed to talk for hours about what we loved: art, design and visual merchandising. By our third Monday morning meeting, I realized I should be taking notes. Over the course of two years, I compiled more than a hundred pages of wit and wisdom from this wonderful wizard of the show window, Raymond Mastrobuoni.

Ray was responsible for 40 years of art and artistry in the windows of Cartier’s Fifth Avenue flagship store in New York City. Over the course of four decades, Mastrobuoni installed five windows every two weeks and never once duplicated a concept. “Pique their interest, compel them to stop, look and think,” was his guiding principle. “Don’t present the obvious, encourage them to hunt and discover.”

While diminutive in physical stature, he was a giant of a man, both in what he accomplished professionally, and in how he touched many lives. This past January 2019, Ray Mastrobuoni passed away at the age of 78, leaving a rich legacy of artistic mastery through his selected medium, Cartier’s acclaimed windows. For Mastrobuoni, inspiration was everywhere and everything was a potential subject for his art. What follows are just some of my favorite stories from this visionary, whose heart was as ubiquitous as his talent (be sure to check out “In Memorium” on page 40 of VMSD’s April 2019 issue, which also honors his legacy):

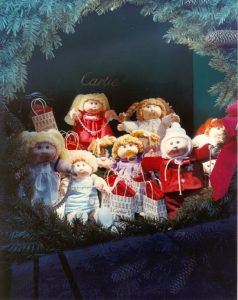

Mastrobuoni always remained true to his simple philosophy when endeavoring to have passersby look at his window displays: “Use current events of the day.” It was Christmastime in New York and Cabbage Patch Dolls were all the rage. Everyone was hunting for them; everyone had to have one for their kids. But they were nearly impossible to find. He went directly to Ralph Destino, then president of Cartier, and told him of his plans to use the cuddly creatures in the windows. Destino happened to have one on his desk, and was happy to lend it to Mastrobuoni.

“One doll won’t make a window,” said Ray, “but I’ll be happy to take it.”

Mastrobuoni asked his wife if her friends had any that they were planning to give to their kids. Ray had a plan: He would borrow the rest of the dolls from children who had them. Destino thought it was a great idea and wanted each doll in the window to wear a $1 million necklace When the window opened for Christmas with the dolls decked out in Cartier's finest jewels, busloads of children came to see the event. A headline in the local tabloid read, “Guards to protect dolls, not kids or jewels.”

Advertisement

Mastrobuoni quickly realized that the children had given all of the dolls names. There was Mary and Alice, and Wendy, and a host of others. This, of course, triggered another idea. Ray handmade tiny Cartier shopping bags with small thank you cards saying, “Thank you for letting me spend two weeks in Cartier’s window.” Sterling silver rattles were engraved with each doll’s name together with a photograph of little Mary or Alice in the window with a bejeweled necklace.

A few days before Christmas, a customer came into the store and said he would take the necklace, but only if it came with the doll. Mastrobuoni said, “They’re coming out of the window next week, but there is only one doll that you can have, the one donated by Destino. The rest go back to the children, they’re only on loan.” Once again, his philosophy rang true. “All displays are representative of current events. This stopped traffic because everyone was aware of the excitement generated by the Cabbage Patch Dolls.”

Another one of my favorite Mastrobuoni miracles occurred during a window washers’ strike. Everyone was aware of the work stoppage in all of the buildings in New York, with special attention given to Fifth Avenue and the retail stores with their large show windows. When the stores on Fifth Avenue dared to clean the windows themselves, they would be sure to find egg-splattered glass – or in extreme cases – broken windows the next morning. Tensions were running high that summer and tempers were as hot as the scorching midafternoon temperatures.

Mastrobuoni got the message. He knew no one was happy about the prevailing conditions and thought he would diffuse the situation with a bit of good-natured fun. He conducted a solo brainstorming session as he pondered what he could do in his window to lighten the mood. As luck would have it, the summer humidity broke on his drive home that night during a sudden and ferocious thunderstorm. On went the windshield wipers, and on went the thinking cap. As the thumping wipers struggled to keep the windshield clean, Ray knew exactly what his window statement would be. What fun, he thought it would be, to have wipers inside the window flipping back and forth, cleaning the inside of the glass while poking fun at the strike.

So he decided to incorporate a stream of water running inside the window while wiper blades whisked the water aside from inside the glass. The idea was solid, but it had to be properly engineered. The intent was to use an actual windshield wiper motor so the wipers would move in sequence. Each of the five windows had wipers going at the same interval, working in unison, like a car. To complete the mechanics, Ray positioned a pan under the window to capture the falling water. A pump recycled the water through copper tubing and across the window, where it was released again, and allowed to flow across the top of the window and down the face of the glass.

The swishing wipers cleaned the windows from the inside and simultaneously revealed magnificent aquamarine stones set in Cartier necklaces, rings and bracelets. Mastrobuoni added much-needed levity to a serious situation. "Let's have some fun with it; let's make people smile," he said. The tensions of those contentious days were cut, as even the striking window washers laughed at the clever windows. Tap into the issues of the day – this was Mastrobuoni’s tried-and-true recipe for success.

Advertisement

Italian week on Fifth Avenue was always a favorite of Mastrobuoni’s. The stores on the avenue would celebrate the week with window displays dedicated to Italy. Awards would be given for the best window presentation, and the winner would get a trip to Italy. Mastrobuoni won first prize three years in a row. After winning the first year, he decided that his assistants should go to Italy for the next two years. His first set of Italian windows were based on Italian food. A grouping of zucchinis, garlic and prickly pears cleverly represented the red, white and green of the Italian flag. Mastrobuoni, being of Italian descent, chuckled when he remembered, “The store smelled like a pizzeria.”

Another year, a serving of pasta was deliciously placed in a colander. Of course, as was Mastrobuoni’s way, the colander was gold plated. Two forks hovered above, appearing to toss a jeweled necklace as though it was an offering of pasta. Naturally, the pasta had a short shelf life in the heat of the windows. Every couple of days his Aunt Anna would bring in a fresh bowl of pasta to keep the windows crisp. Mastrobuoni took great pride in the fact that objects he created in the windows often became Cartier products. The gold colander became an object of desire for all who saw the windows. Mastrobuoni suggested making them smaller. A three-inch gold colander was made, and Cartier offered it for sale. Then two smaller sizes were made, and customers kept buying the smaller version. They sold like hot cakes.

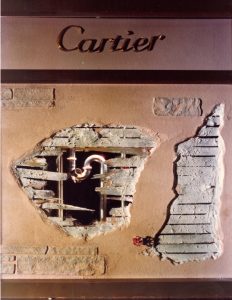

Perhaps my favorite Mastrobuoni creation was inspired by his wife Helen. One evening at the dinner table, Helen suggested that he come up with a window about a diamond ring tragically lost in a drainpipe. She continued, explaining that many women accidentally drop their rings down the kitchen sink. Mastrobuoni’s response to Helen was, "When I run out of ideas, I will use your idea." He filed her suggestion in his mind, until a few months later when the time arrived.

A few of Mastrobuoni’s cousins were in the construction business. Hearing of his challenge and Helen's inspiration, they took him to one of their construction sites in the Bronx where they were doing a building renovation. Mastrobuoni asked to see the kitchen. They showed him a wall that still had the remnants of a kitchen sink. Mastrobuoni asked for a sledge hammer and proceeded to bang a hole in the wall. He wanted to see what the inside of the wall looked like along with the inner workings of the sink. As he broke through the layers of wall and broken mortar, he exposed hidden wooden slats, chicken wire mesh and the drainpipe. He then asked for a section of the wall, complete with the wooden lath, to bring back to his laboratory/studio.

Back in the studio, Mastrobuoni created a master for the window, built out of deco brick, wooden slats and plaster. From this, he created a mask that fit perfectly into the Cartier window. The next step was to buy a drainpipe from a plumbing supply store. Before installing the pipe in the window, Mastrobuoni cut a hole in it so that the viewer could see the diamond ring trapped inside. Then Mastrobuoni added a finishing touch: a red faucet as a shot of color. The ring was positioned in the drainpipe, and a spotlight was focused to highlight the stone. The picture was complete.

Mastrobuoni was a true visionary. His career bridged the gap between “display” and “visual merchandising.” With a wide array of tools, ranging from hot glue guns to sophisticated computer applications, Mastrobuoni was part of a grand evolution that ushered the visual merchandising profession into the 21st century.

Advertisement

The industry is saying goodbye to an important creative sensibility. The overriding message of his remarkable 40-year journey was: “To impart mind to medium. Don’t be afraid. With a little creativity you can do anything.” I will be forever grateful for the friendship we shared.

Eric Feigenbaum is a recognized leader in the visual merchandising and store design industries with both domestic and international design experience. He served as corporate director of visual merchandising for Stern’s Department Store, a division of Federated Department Stores, from 1986 to 1995. After Stern’s, he assumed the position of director of visual merchandising for WalkerGroup/CNI, an architectural design firm in New York City. Feigenbaum was also an adjunct professor of Store Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology and formerly served as the chair of the Visual Merchandising Department at LIM College (New York) from 2000 to 2015. In addition to being the Editorial Advisor/New York Editor of VMSD magazine, Eric is also a founding member of PAVE (A Partnership for Planning and Visual Education). Currently, he is also president and director of creative services for his own retail design company, Embrace Design.

Photo Gallery7 days ago

Photo Gallery7 days ago

Headlines6 days ago

Headlines6 days ago

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines2 weeks ago

Headlines2 weeks ago

Designer Dozen2 weeks ago

Designer Dozen2 weeks ago

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines1 week ago

Special Reports2 weeks ago

Special Reports2 weeks ago

Designer Dozen5 days ago

Designer Dozen5 days ago