From Cobblestones to Cyberspace: VMSD Celebrates Its 125th Year of Service to the Retail Industry

We trace retail’s evolution from 1897 to present day

Published

1 year agoon

PROGRESS AND ENLIGHTENMENT

In 1897, William McKinley was sworn in as the 25th President of the United States, Thomas Edison patented the Kinetoscope, and The New York Times began using the slogan “All the News That’s Fit to Print.” Poised on the threshold of the 20th century, the world looked toward the future with hope and optimism. But even the most forward-looking could not have visualized the enormity of change that lay ahead.

The relentless march of progress was exponential, and retail as we know it today was in its formative stages. Captivated by technology and industrialization, entrepreneurs such as Henry Siegel and John Wanamaker visualized a new retail format. Emboldened by the expanding railroad system, cast iron architecture and the harnessing of electricity, a new and dynamic entity began to take root in major industrialized cities across the world.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, well before high-end shops and boutiques graced the iconic retail corridors of Fifth Avenue, Champs-Élysées and Via Monte Napoleone, consumerism and desire became a driving force in Western culture. Major cities from the U.S. East Coast to the boulevards and avenues of Paris and London were the spawning grounds for grand commercial buildings that housed everything from pots and pans to glamorous evening gowns.

New York quickly became the epicenter of burgeoning new retail concepts. Ladies Mile – a section of Manhattan bounded by 23rd Street and 8th Street, between Broadway and Sixth Avenue – symbolized a more opulent time. Gaslight lamps and cobblestone streets were the order of the day. Stylish patrons seeking the latest fashions from shirtwaists to wing collars, and the finest of fabrics, flocked to an impressive roster of newly founded department stores including The John Wanamaker Store (designed by Daniel H. Burnham, architect of the Flat Iron Building), James A. Hearn & Son, B. Altman, Hugh O’Neill (with its wonderful Corinthian columns), Lord & Taylor (with its mansard roof and cast-iron dormers), the esteemed Arnold Constable, and the Beaux-Arts style Siegel and Cooper (then the largest store in the world).

The original Stern Brothers Store on 23rd Street, between Fifth and Sixth avenues, is still in mint condition today. It’s a great example of cast iron architecture, which – coupled with the availability of plate glass – was a keystone to merchandising theater. These building technologies, with the ability to span large spaces, led to the development of the show window. These innovations were the sparks that led to the inception of the visual merchandising and store design industries.

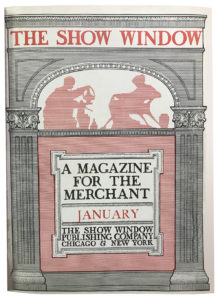

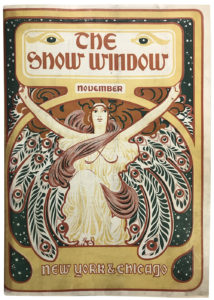

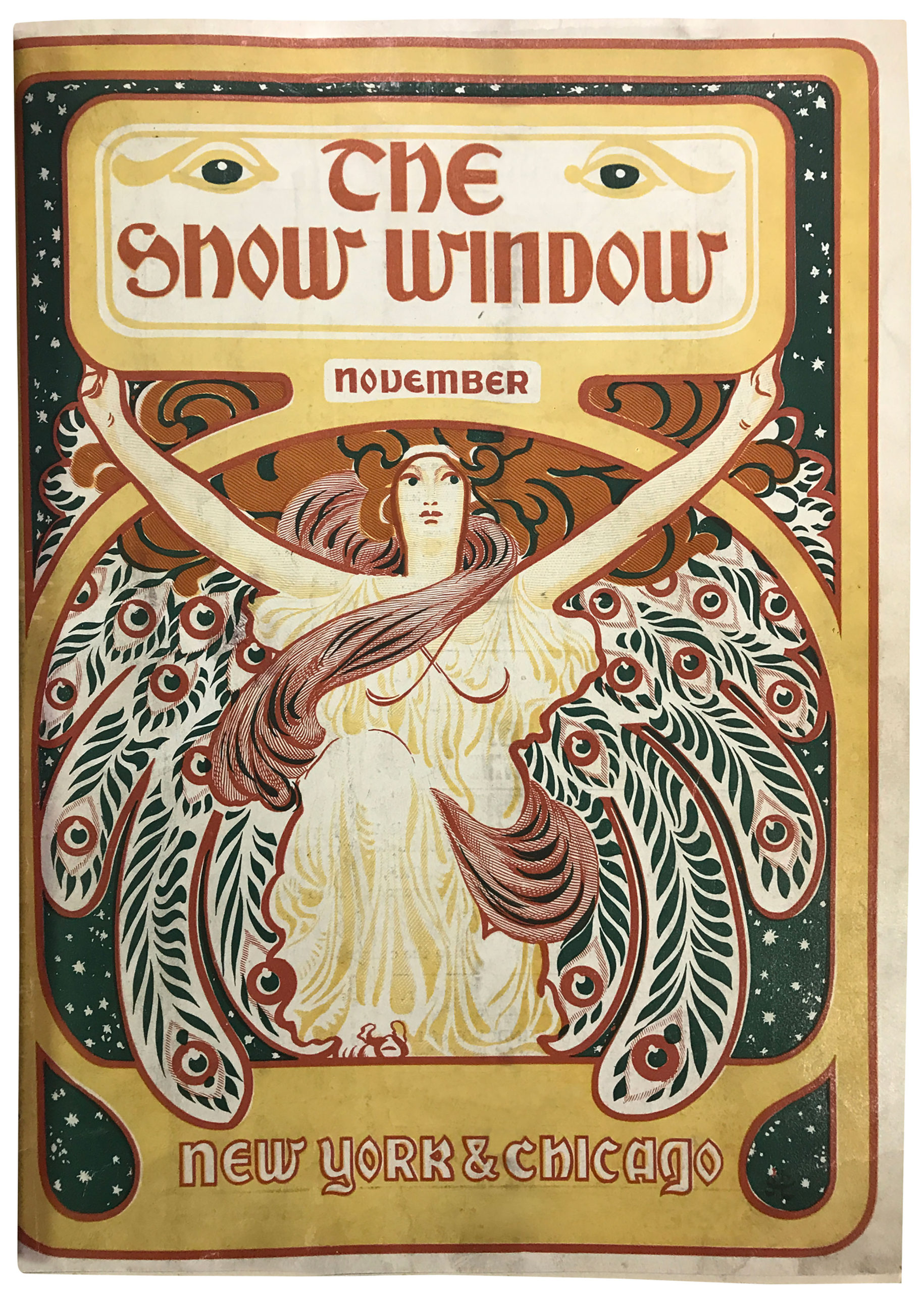

AdvertisementAnd while these megastores were in their seminal stages, nobody quite knew what to do with them and the unending mountain of merchandise sitting under their roofs. Nobody except a young man named L. Frank Baum, who edited The Show Window in November 1897, a periodical devoted to the presentation of merchandise. Originally based in Chicago, it was purchased by Cincinnati-based ST Publications (later renamed ST Media Group) and eventually merged with its competitor at the time – Display World – in 1938. Throughout the decades, it has been known by various names, including The Merchants Record & Show Window, Visual Merchandising, VM&SD, VM+SD and VMSD.

In one of the first editions of The Show Window, billed as a monthly “Journal of Practical Window Trimming,” Baum enthusiastically wrote, “Suggest possibilities of color and sumptuous display that would delight the heart. Bring the goods out in a blaze of glory, make them look like jewels.”

“When Merchants Record & Show Window debuted in 1897, it was cataloging the ideas of massive store windows as retail honey traps for miladies promenading on the main streets of U.S. cities,” says Steve Kaufman, former Editor-in-Chief of VMSD from 1998 until 2009. “And its editor was a sometimes-writer named L. Frank Baum, who famously looked across his office at the file cabinets labeled A-N and O-Z and had his name for the fictional empire and its wizard in a story he was laboring over,” – as the story goes.

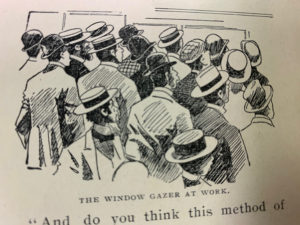

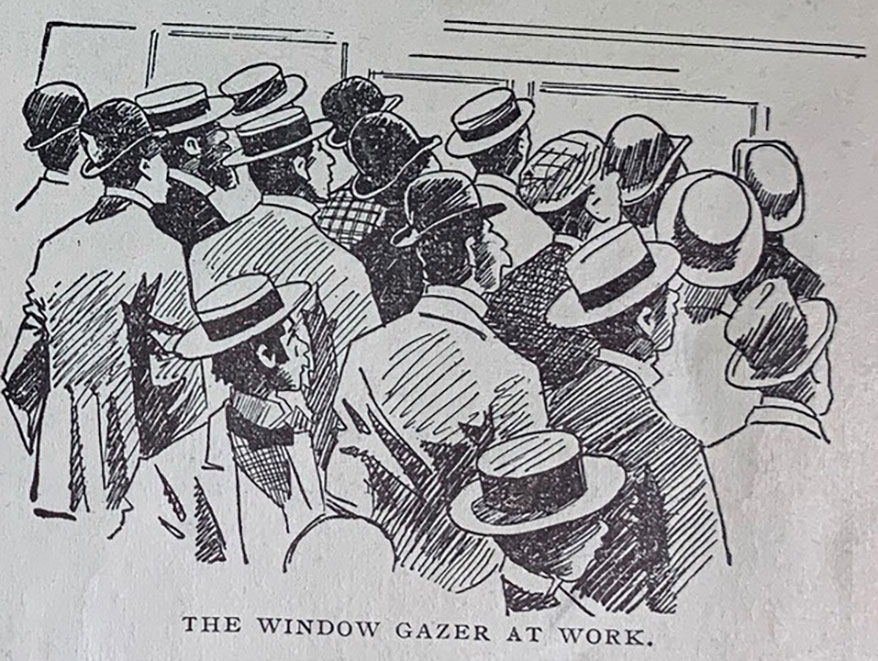

This illustration from an early 1900s issue is captioned, “The window gazer at work.”

A couple years after publishing The Show Window, Baum went on to write the beloved American classic, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” And while the tales of Dorothy, Toto and the Tin Woodman captivated readers across the world, the publication evolved into the ever-present VMSD magazine, the industry’s oldest and most influential publication.

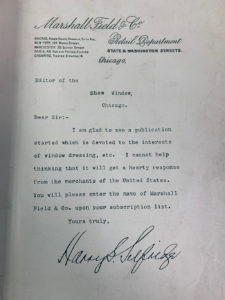

Within a few short months of its debut, circulation grew into the tens of thousands. One of its first supporters was Harry Gordon Selfridge of Marshall Field’s, who went on to found Selfridges in London.

AdvertisementOver the course of the next 125 years and through the ensuing decades, VMSD took readers from the cobblestone streets of Ladies Mile to the outer reaches of cyberspace. “One of my favorite things about VMSD is its history with L. Frank Baum,” says Joe Baer, Co-Founder, CEO and Creative Director of ZenGenius Inc. “Visual merchandisers come from all sorts of creative backgrounds, and when I realized that VMSD was started by the greatest storyteller ever, it helped me appreciate the rich history of the magazine and the power our creative efforts can make on the world.”

A true thespian at heart, Baum drew inspiration from the theater, seeing a connection between performance art and retail presentation. He wrote about fanciful props, imaginative themes and the use of color and lighting to capture the attention of passersby. His theatrical instincts led him to suggest the hiring of actors to work as professional window gazers. In that role, he envisioned “a well-dressed gentleman of respectable appearance.” Baum explained in the first issue of The Show Window, “He comes down the street at a swinging pace, glances casually at the window, and then abruptly stops to gaze eagerly at the goods displayed.”

Changing attitudes and emerging technologies in the early years of the publication sparked new approaches to mercantile design. The turning calendar welcomed an era of progress and an age of enlightenment, offering broader educational opportunities, greater access and extended avenues of communication. As the industrial revolution continued to churn, an agricultural society evolved into a manufacturing powerhouse. A new and distinct culture was born – business oriented and commerce driven. As the 1800s gave way to the 1900s, necessity was yielding to desire. Soon, people wanted more and more.

“A magnitude of goods were produced to satisfy the needs that no one knew they had,” wrote Emily Fogg Mead. “Consumers wanted berry spoons, mustard spoons, sugar spoons, and soup spoons in ever increasing variety.”

In the previous century, little thought had been given to the aesthetic arrangement of merchandise or the visual appeal of the store. Goods were haphazardly displayed in disorganized stacks and piles, or carelessly hung on columns and railings. Goods that weren’t scattered across walls were often hidden in drawers, out of sight and reach. The term “customer friendly” did not apply.

As merchants stared into the face of the new century, philosophies began to change. Retailers now considered welcoming gestures that invited customers into the store. A single architectural initiative, the dismantling of the doorstep, was a compelling statement. It was soon understood that a step at the entrance was a mistake. “No hindrance should be offered to passersby as they enter the establishment,” said John Wanamaker. In addition, aisles were widened, and outdated swinging doors were replaced with revolving doors. Access was made easier with multiple entrances from the sidewalk. Wanamaker boasted that no other large store in the world had as many entrances as his grand emporium in Philadelphia.

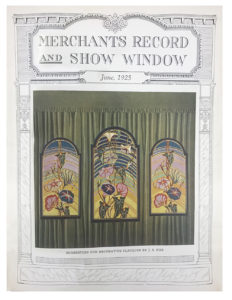

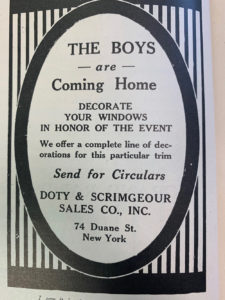

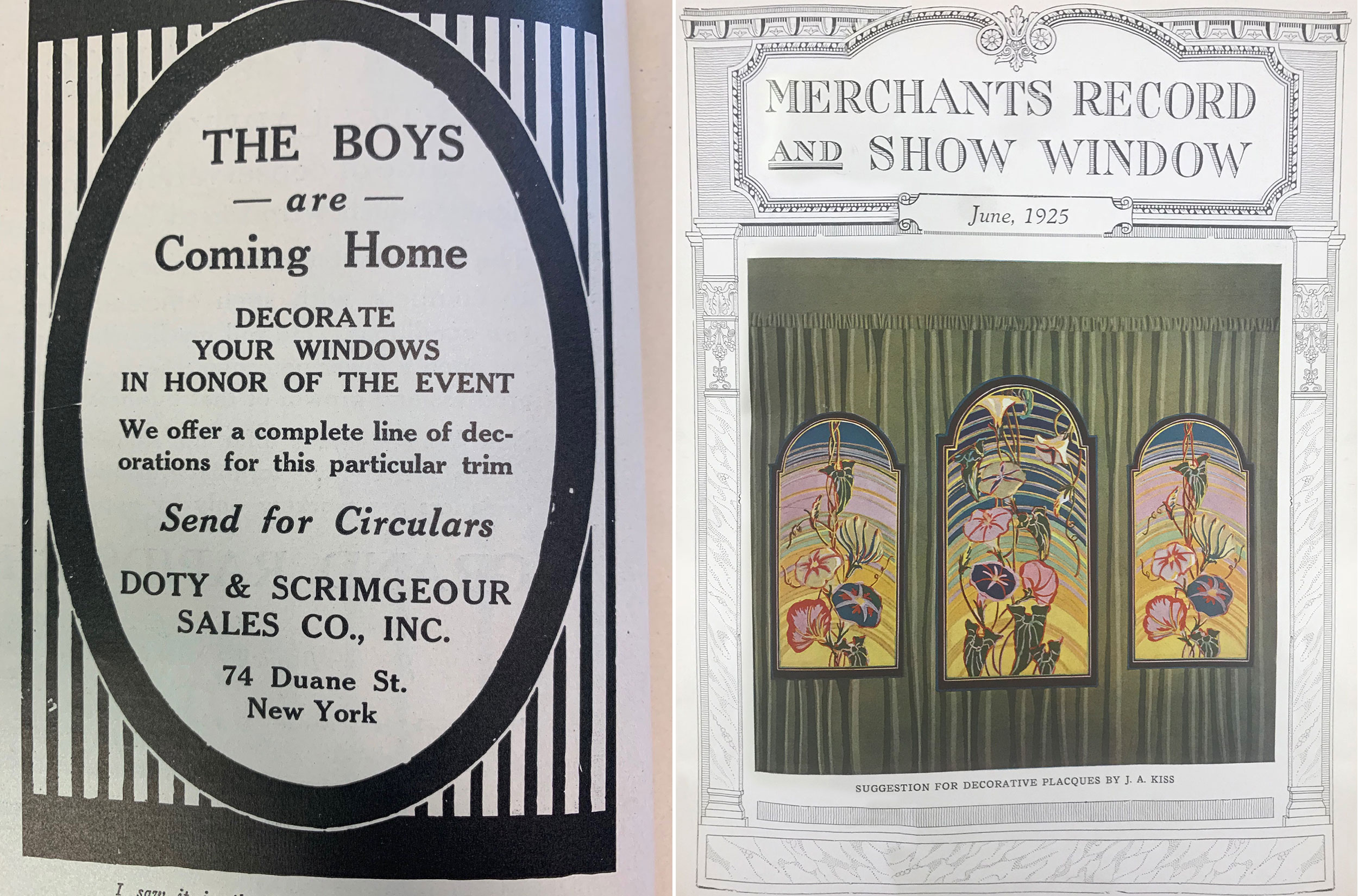

Advertisement  Right, Left: An advertisement for decor references the return of American soldiers from WWI (left). The June 1925 cover of Merchants Record and Show Window features a floral, art deco-inspired theme.

Right, Left: An advertisement for decor references the return of American soldiers from WWI (left). The June 1925 cover of Merchants Record and Show Window features a floral, art deco-inspired theme.

THE END OF THE

BELLE EPOQUE

In the early 1900s, Baum resigned from the editorship of the The Show Window, leaving behind the framework of an enduring industry publication and the foundation of a new and dynamic profession. He believed that merchandise presentation was an art form. As such, visual merchandising was born.

By 1910, show windows were becoming an important tool for entrepreneurs across the retail spectrum. As a theatrical approach to merchandising was beginning to evolve, clever “displaymen” used fantasy and theater as aspirational enticements. In 1913, the windows at Marshall Field’s in Chicago displayed a line of merchandise inspired by Japanese culture and tradition. Arthur Fraser, recognized as the most prominent display director of the decade, celebrated the theme with a series of large Japanese landscapes. The Merchants Record and Show Window wrote: “The soft, hazy tones and vague lines, with the faint, snow-capped Fujiyama in the distance, gave wonderful perspective to the whole setting.” Marshall Field’s traditionally covered its windows on Sundays, pulling down drapes to discourage window shopping on a day of religious observance. Unexpectedly, the Monday morning unveiling of the windows increased anticipation as thousands assembled to see Fraser’s weekly spectacle. When Fraser started at Field’s, his display department consisted of just seven people. By 1916, Fraser led a staff of 50.

Show windows began to proliferate across the retail landscape. A walk down any retail corridor was akin to a walk through a crystal wonderland; window displays were ubiquitous. By 1915, Americans were reportedly consuming half of the global production of plate glass.

An advertisement in the August 1917 edition of Merchants Record and Show Window proclaimed that the Koester School was “The Greatest Window Display School in the World.”

Retail advanced in a time of hope and of despair. A peaceful century succumbed to worldwide war, and extravagance yielded to discretion. The ravages of The Great War were to spawn movements in art and literature. Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and the other German Expressionists portrayed the human condition while poet John McCrae famously wrote, “In Flanders fields the poppies blow between the crosses, row on row…”

And, undeterred by global theater and international events, commercialism persevered and flourished as America continued to grow. As the decade began, a new and creative approach to retailing began to evolve. Goods were infused with associative qualities, connecting them to people, places and events. The show window was fast becoming a selling stage. Macy’s 1914 spring window extravaganza allowed customers to stroll down a promenade on the French Riviera as mannequins cloaked in luxurious evening gowns were staged in an opulent ballroom.

In 1919, Merchants Record and Show Window published an article titled, “Enhancing the Value of the Store Front.” That same year, soon after World War I, Gropius introduced the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany. The movement was influenced by modernism and constructivism, and had a significant impact on architecture, graphic and industrial design, fashion and even music.

When the war ended, the boys came home from France. But another powerful army was marching across the landscape: the major corporations of America. It was an age of big business, mergers, conglomerates and large capital investments. The age of demand returned, but now it was the insatiable demand of big business.

At the end of WWI, Merchants Record and Show Window ran an advertisement by Doty & Scrimgeour Sales Co. Inc. for store window decorations in honor of the returning soldiers.

SELL THEM THEIR DREAMS

The period between the World Wars and the uncertainty of the Great Depression spawned the art deco movement (perhaps the most influential period of design in the 20th century), greatly impacting all creative endeavors, including visual merchandising and store design.

The July 1920 edition of Merchants Record and Show Window boldly reported, “The Displayman is the Great Dis-Coverer of Business. What the fire is to the Engine – What the ‘juice’ is to the Motor. So is the Displayman to modern business. He is the force that makes things move. Might as well board up the windows if Display is to be neglected.”

In 1922, Display World began publication in Cincinnati and quickly became a competitor to Merchants Record and Show Window, as interest in the industry grew. Helen Landon Cass, a popular radio personality of the time, told a display convention in 1923: “Sell them their dreams. Sell them what they longed for and hoped for […] Sell them this hope and you won’t have to worry about selling them goods.”

The theatrics and enticements continued in 1924 as Macy’s held its first Thanksgiving Day Parade. Called the Christmas Parade, it covered a five-mile route from Harlem to Herald Square. The participants were mostly Macy’s workers and immigrants who missed the festivals that were common in Europe.

The strategic seduction of the masses was fueled by three A’s: advertising, art and air conditioning. In 1925, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover said, “The Midas of advertising has given artists freedom and independence.”

Sherwood Anderson, John P. Marquand and F. Scott Fitzgerald were writing ad copy. The paintings of Georgia O’Keefe were seen in the windows at B. Altman’s and Marshall Field’s; the murals of Boardman Robinson graced the walls of Kaufmann’s. The power of advertising and the enrichment of fine art were reinforced by a commitment to customer comfort. Retailers now prolonged the selling season into the dog days of summer thanks to the magic of air conditioning.

In 1928, Frederick Kiesler of Saks Fifth Avenue created what he called America’s “first representative exposition of modern show windows.” The use of modernism in the retail environment brought with it a sense of simplicity, allowing the viewer to focus on the goods. Kiesler spoke of his “spotlighted” windows: “Accent one chair – one white fur. One sees only a chair – a white fur collar.”

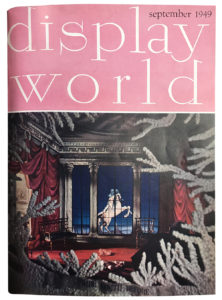

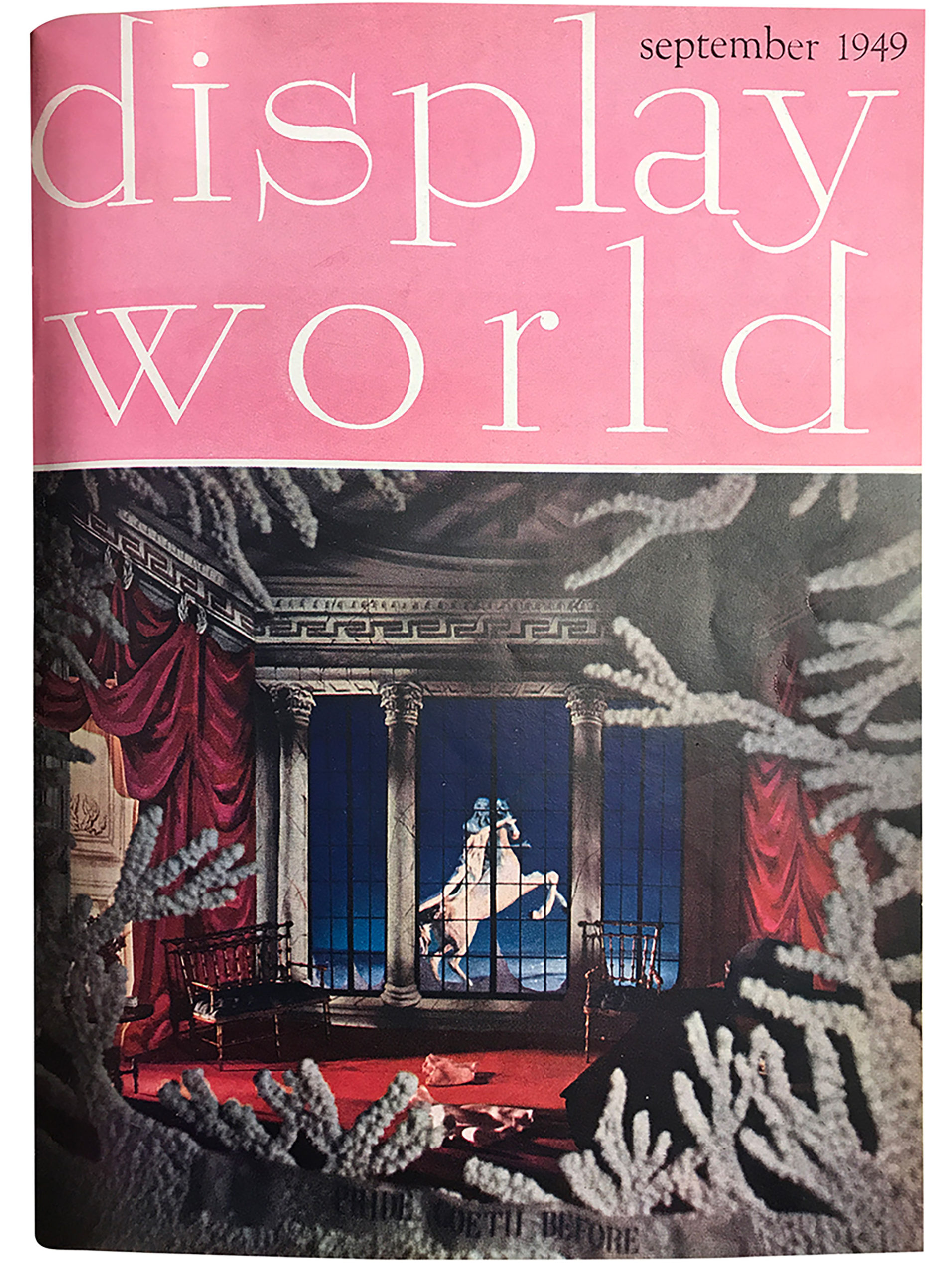

The Sept. 1949 cover of Display World highlighted a jewelry display created by the legendary Gene Moore, a longtime Tiffany & Co. window dresser.

The Sept. 1949 cover of Display World highlighted a jewelry display created by the legendary Gene Moore, a longtime Tiffany & Co. window dresser.

ELEGANCE, ESCAPISM AND

THE GOLDEN AGE OF DISPLAY

In 1931, the famed mannequin designer Pierre Imans modeled a mannequin after French jazz legend Josephine Baker. Iman’s creation was the epitome of art deco design, with its elongated hands and facial features, in addition to the subtle bend of the neck.

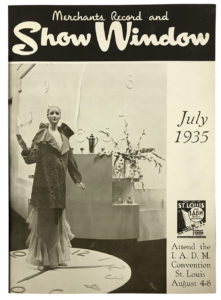

In sharp contrast to the harsh realities of the Depression, the 1930s was the most elegant period in Hollywood’s history. And retail took its cues from the movies. In 1935, Cora Scovil, a renowned mannequin sculptor and window dresser, captured the attitude of Hollywood’s elite in a series of mannequins bearing the likenesses of Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo and Joan Bennett. And Lester Gaba produced a series of papier mâché mannequins modeled after Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Carole Lombard. (Gaba was a premiere mannequin sculptor who brought his much-loved “Cynthia” with him everywhere he went. Cynthia hadn’t a heart; she weighed in at 125 Plaster of Paris pounds.) Through the influence of Scovil and Gaba, mannequins assumed a new posture in American retail.

The world was changing exponentially in the waning years of the 1930s, and retail was following suit. In 1938, Merchants Record and Show Window ceased publication and merged with its competitor Display World. “Over the years, the magazine meandered in from the sidewalk and into the stores for a new focus called Display World,” says Kaufman. “Show Window was a name anyone could relate to. Display World was a concept familiar only to those who created those magical windows and in-store merchandising presentations and holiday extravaganzas with their new tools of props and mannequins.”

In 1939, Montgomery Ward advertising copywriter Robert May needed to come up with an enticement for Santa to give to children. Unknowingly he created one of the most enduring Christmas characters the world over, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Approximately 2.4 million copies of May’s endearing Christmas tale were distributed. Ten years later, Johnny Marks put the story to music, and the song became a massive hit for the singing cowboy, Gene Autry.

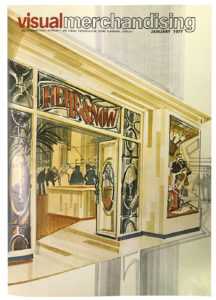

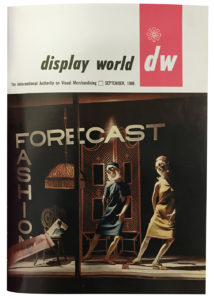

Our Sept. 1979 issue focused on signage and graphics with a detailed, illustrated cover.

Our Sept. 1979 issue focused on signage and graphics with a detailed, illustrated cover.

PROSPERITY AND MOBILITY

As the ’30s gave way to the tumultuous ’40s, The National Association of Display Industries was founded in New York City. That same year the U.S. entered World War II, creating shortages in personnel and materials. Due to wartime rationing, mannequins became shorter to conserve materials. Tall mannequins and cuffed pants were considered wasteful and unpatriotic.

As the war raged on in Europe, America became isolated from the influence of Parisian fashion and searched for its own signature. Voila! A new generation of American designers included Claire McCardell, who originated the “American Look,” inspired by the working garb of the nation’s farmers, railroad engineers, soldiers and sportsmen. McCardell and her contemporaries put their stamp on a more casual attitude. The basic construction of American sportswear was compatible with mass production, greatly influencing international fashion, store design and visual merchandising.

In 1945, the end of WWII prompted a dramatic economic upturn and population explosion. As the baby boomer generation was born, sales at Sears exceeded $1 billion. With the battle-weary men returning home after the war, women re-embraced traditional roles, leaving the workforce for the household. Fashion responded with longer, fuller, more feminine skirts with thin, fitted waists. Seizing the moment, Mayorga Mannequins introduced a line of “Welcome Home Mannequins” featuring the outstretched arms of a young couple and the longing gaze of their little girl. It was a quest for tranquility. Young American families searched for a new life, a new start and an escape to a new world.

By 1946, a frenetic postwar building boom had a great impact on downtown stores. By 1947, more than half of America’s households had automobiles. Affordable housing, wash-and-wear fabrics and suburban shopping centers were becoming exceedingly common. With an uptick in automobile traffic, a trip downtown became less desirable. Suburban stores began to blossom with broad merchandise offerings as downtown merchants struggled to maintain their client base.

An advertisement for D.G.Williams Inc. in the August 1948 edition of Display World reads, “A Macy’s Grows In Brooklyn. Opening of the new Brooklyn Macy’s poses the familiar question: Whose mannequins will model the Macy merchandise? Answer: Mary Brosnan’s. And why has Macy’s chosen Mary Brosnan mannequins despite the blandishments and special inducements of other makers? Answer: Because Mary Brosnan mannequins are the dominant, sales making beauties of the Visual Merchandising world.”

In North Carolina, Belk’s maintained a healthy confidence in their downtown locations. In 1948, Hudson-Belk decided to improve its Fayetteville Street store in Raleigh, N.C., rather than abandoning it in the wake of changing times. The city’s first escalators were installed to great fanfare. One young customer was inspired to say, “It’s like going right up to heaven!” Scarcely did he realize that heaven would have a suburban zip code.

MID-CENTURY, AN

AGE OF AWAKENING

Culturally, the 1950s was the decade of Mies van der Rohe and Ozzie & Harriet, Hollywood Cinemascope and Hollywood blacklists, Frank Lloyd Wright and Elvis Presley, gray flannel conformity and cuffed jeans irreverence. It was the decade of McCarthyism, nuclear fears, beatnik poetry and the hula hoop. It was also the decade of suburban sprawl. Economic expansion was fueled by a new affluence. Post-war America’s patchwork of suburban communities – single-family homes sprouting quickly like mushrooms across the landscape – were connected by highways of enthusiasm.

In 1950, B.B. Butler Mfg., Chicago, advertised PegBoard in Display World. This innovation led to other self-selecting fixtures such as rounders, four ways and T-stands. The advancing decade also provided visual merchandisers with foam board and a new interlocking fabric called Velcro.

In 1951, Victor Gruen, an Austrian-born architect, philosophized that if suburban communities were to survive, they must provide places for people to interact. Gruen presented a progressive vision to Minneapolis-based Dayton’s department store: two competing department stores in the same center.

That same year, Stanley Marcus started the Neiman Marcus art collection, the largest of any retailer in America. In the ensuing years, Neiman Marcus continued collecting, considering art an important part of their store environments.

In 1955, an article in Display World titled “Projection of Store Personality,” read, “It is flashes of personality traits that make the Lord & Taylor customer feel at home in any Lord & Taylor store. While this is an acquired art, not easy to achieve, it is worth striving for in any branch store.”

The December 1957 issue of Display World profiled the new Saks Fifth Avenue store in Springfield, N.J. The display director Joseph Rouse said the store relied on a multiplicity of elegances such as satin covered dress forms, to create the overall feeling of luxury. Advertisers at the time included the A.L. Hansen Mfg. Co., Chicago, the makers of the visual merchandiser’s most important tool, the tacker. The ad described the relationship of the professional display-man and his tacker as “inseparable.”

AdvertisementCOUNTER-CULTURE AND

THE AGE OF AQUARIUS

In 1966, a London-based mannequin manufacturer premiered an innovative modern mannequin, with realistic movement and uniquely human qualities. Slim-limbed Twiggy, wiry Sandie Shaw and seductive Luna (the first widely recognized black mannequin) highlighted the company’s line and defined a new mannequin attitude.

If the ’60s was British insouciance, it was also French stylishness. As Yves St. Laurent began opening small Rive Gauche shops around the fashion world, American merchants adopted the French term boutique for the first time. Large U.S. department stores were soon feeling the effects of this new form of “shop” shopping. In New York, Henri Bendel opened the Haze Glazebrook-designed Street of Shops on its main floor. Inspired by the Via Mizner in Palm Beach, this was the first grouping of boutiques within a single large-store environment.

In 1960, Display World championed a new material called Fomecor. An advertisement for the National Equipment Corporation said, “You can do almost anything with new Fomecor.” Limited only by their imagination, a generation of display artists went on to create magic with this versatile new material.

In 1968, Bloomingdale’s began to stock ties by a then unknown designer named Ralph Lauren, and a year later Donald and Doris Fisher open the first Gap store in San Francisco. In keeping with the ever-evolving industry, 1973 brought another name change to the magazine, from Display World to Visual Merchandising.

During the transitional years of 1968 to 1972, American youth dissociated itself from bygone eras, values and traditions. As the ’60s slipped into the ’70s, the counter-culture produced a new couture and the streets produced a new anti-fashion. The nuances of the street dominated fashion while “street theater” defined fashion windows. In 1976, Rosemary Kent coined the term in her New York Times piece on the new trend in fashion windows. With New York “street artists” setting the pace, this window genre soon spread across the country.

Social awareness brought a new sense of realism to mannequin design. In 1972, Henry Callahan designed the “Contessa” mannequin for Saks Fifth Avenue’s windows. A dramatic departure from the aloof, unblemished beauty of past mannequin creations, she represented a woman in her mid-30s who, though of regal bearing, looked totally human. The decade’s most telling mannequin innovation, however, was also a by-product of street theater. Increasingly, mannequins were designed to be sold as sets or groupings.

MERGERS, ACQUISITIONS

AND A SEARCH FOR IDENTITY

In december 1982, Visual Merchandising introduced Peter Glen’s monthly column which quickly became a reader favorite. Then in 1983, Visual Merchandising changed its name to Visual Merchandising and Store Design. A year later, in the 1984 movie “Moscow on Hudson,” Robin Williams decides to defect in the middle of Bloomingdale’s.

The advancing decade began to obscure baby boomer idealism. The Hippies of the 1960s and ’70s had become the Yuppies of the 1980s – materialistic, narcissistic and acquisitive. The “Me” generation was reaching its earnings peak and trading beads and flowers for power ties and dress-for-success outfits. Shopping became a sport, with fashion as the ultimate prize.

But over-optimism fueled over-spending, over-borrowing and over-expansion – ultimately leading to over-storing. A rash of liquidations, acquisitions, mergers and restructuring plagued the department store world, and 1986 was a year of monumental change. Canadian real estate developer Robert Campeau turned the industry upside-down when he acquired Allied Stores Corp., and an employee-led takeover of Macy’s was completed. In that same year, Gimbel’s folded, and May acquired Associated Dry Goods Corp.

Specialty retailers such as Gap, Guess, Limited, Benetton, and Esprit began to offer their own brands. Large retailers tried fighting back with unique environments of their own, but the brands they were promoting – Ralph Lauren, Liz Claiborne, Perry Ellis, Calvin Klein – took on a life of their own, assuming a dominant role on selling floors. Ralph Lauren’s flagship in New York’s Rhinelander mansion was opened. Soon, large retailers were fighting to grab back their identities.

As visual merchandising progressed, the job description changed dramatically. Creativity was still paramount, but a business acumen and merchandising skills became necessary accompaniments.

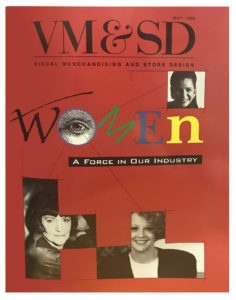

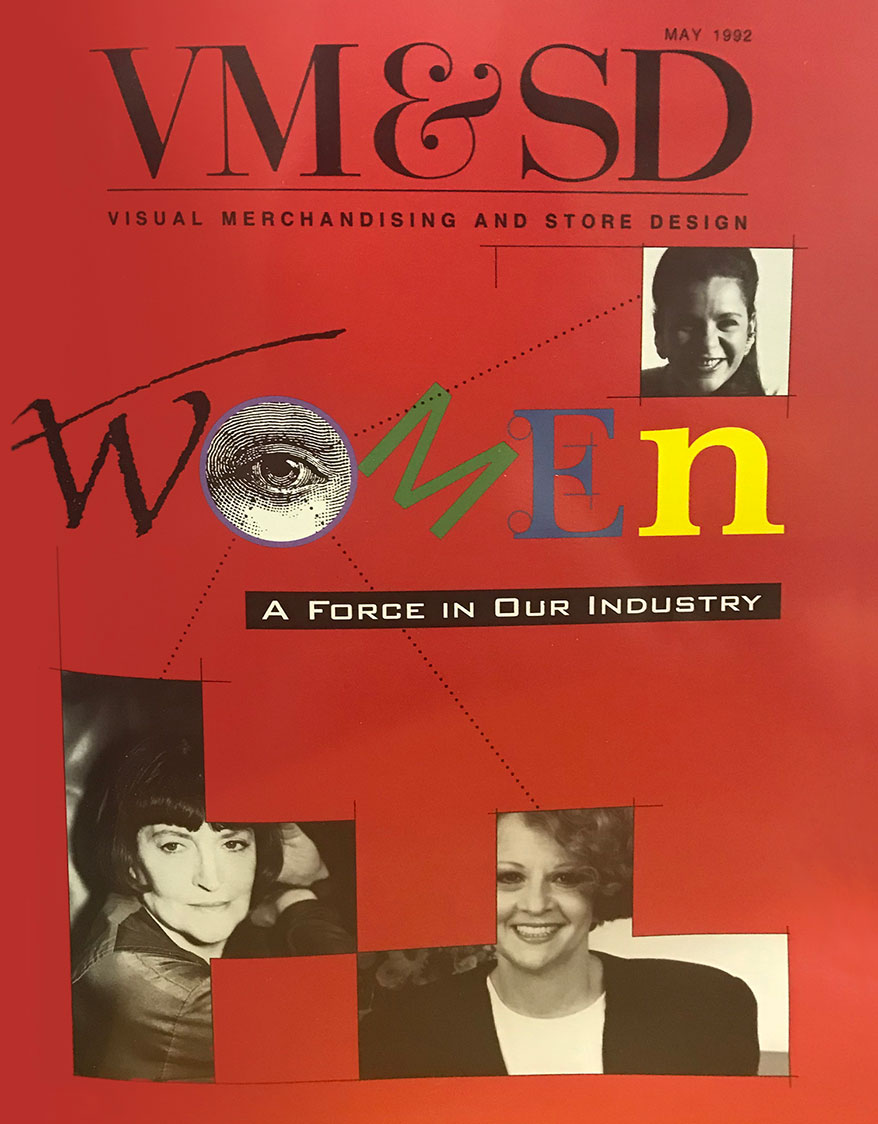

Advertisement The May 1992 issue featured profiles of leading women across an array of retail organizations.

The May 1992 issue featured profiles of leading women across an array of retail organizations.

AN AGE OF AWARENESS

The world wide web spurred global connectivity and global awareness, bringing a cross-pollination of international cultures in the early ’90s. Fashion transcended all international boundaries. Nike T-shirts were on the streets of Taipei and Nairobi, Hilfiger was in Seoul and Manhattan, and Lagerfeld influenced Tokyo and Paris and all points in between.

In the late 1980s, VM&SD began coverage of environmental concerns in a series titled “Earthworks.” The articles covered a wide range of initiatives taken by retailers, from reducing packaging destined for landfills, to how retailers and brands celebrated Earth Day.

The May 1992 cover story of VM&SD read, “Women – A Force in Our Industry.” Profiles of leading women in retail organizations, design consultancies as well as leaders in retail equipment/decor/fixturing manufacturing organizations, continued throughout the year. “The profiles revealed more personal details about each of the women and that resonated with readers,” recalls Janet Groeber, Editor-in-Chief, 1992-1998. “In looking back over the profiles, I’m so impressed with the range of women interviewed and the diversity of the group. We asked these women if they ever felt the constraints of a ‘good old boy’ network impeding their progress in any way. Across the board, they answered with a resounding ‘No.’ in fact, most have found men to be receptive and responsive to their contributions – and respectful of their work.”

In October 1997, Groeber received the ultimate word: a commendation from President Clinton. The president wrote, “In an increasingly competitive marketplace, you can take great pride in your longevity. Your efforts have contributed immeasurably to the economic well-being of your industry.”

The evolution of retail marches in perfect time to the evolution of the cities in which retailers plant their flags. A 2004 article in VM+SD read, “Uptown Girl Goes Downtown,” as Bloomingdale’s opened a new store in one of SoHo’s 19th century cast-iron buildings. In 2009, VMSD reported, “After a multi-year renovation that involved moving departments around like a Rubik’s cube, the revitalization of the main floor of Bloomingdale’s Manhattan flagship was complete.”

Recognizing that kale is the new black, VMSD began covering the fashion of food. A 2006 article reported that as Whole Foods prepared for its 25th anniversary, it opened its biggest store yet, an 80,000-square-foot flagship in its its home base, Austin, Texas.

TECHNOLOGY RULES

The impact retail has had on our lives is undeniable. “For centuries, trading and what we now call retail has been an elixir for humanity,” says Brian Dyches, a VMSD contributing writer. “Daily life, community and innovation have been at its roots since day one.”

The last decade of the 20th century proved to be the zenith of the most dynamic period in world history, ushering in an age of unprecedented technological advances. In the ’90s, cutting-edge technology revolutionized retail with computer-aided design and manufacturing, and electronic purchasing and replenishment. Data transfers that previously took days or even weeks happened instantly. At Federated Dept. Stores, the Visual Directors’ Team used video conferencing to share strategies and selling techniques throughout the entire far-flung organization.

Patricia Sheehan, VMSD Editor-in-Chief from 2013 to 2015, recalls the unprecedented changes in the shopping experience during her tenure. “We witnessed the rise of digital commerce and the challenge to retailers, designers and merchandisers to keep the in-store experience relevant, inviting and invigorating. We saw a renewed commitment to strong storytelling and experiential design, while embracing the technical advances in signage, lighting and fixtures that best served the customer experience.”

Advertisement

YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW

“As we look back at our storied history, it’s almost unthinkable to consider an American magazine that has been in business for 125 years! And not a general interest magazine, like Reader’s Digest or Harper’s,”says Kaufman. “But rather a trade magazine with, by definition, a narrowly defined readership base. And not just a trade magazine, but one whose focus over the years has changed with the times, its ups and downs, ins and outs, trends and changing trends.”

VMSD’s Managing Editor Carly Hagedon says, “I am truly honored to work for such a storied publication. I’m often in awe of how old the magazine really is – many brands are not fortunate enough to have made it to 100 years, let alone 125. I think the fact that we’re still here, and relevant, proves the importance of print and journalism for this industry. Even though we at VMSD embrace our digital channels, it’s nice to see that folks still rely on and prefer the physical medium.”

It would be difficult to understand the last 125 years of retail design without understanding a century of cultural development. Over the years, VMSD has been at the forefront in reporting on cultural movements and technologies that drive retail innovation. Great art, architecture and literature all blend and co-exist. All are reflective of their times and all have made an impact on retail design.

“It’s remarkable that VMSD has been inspiring retail creators for more than a century,” says Murray Kasmenn, VMSD VP Group Brand Director, Publisher. “It’s an honor to be a part of this legacy brand that’s adapted and maintained relevance in our ever-changing industry. I’m excited about what’s next in retail and look forward to VMSD continuing to lead us into the future.”

PHOTO GALLERY: VMSD ARCHIVES

Eric Feigenbaum is a recognized leader in the visual merchandising and store design industries with both domestic and international design experience. He served as corporate director of visual merchandising for Stern’s Department Store, a division of Federated Department Stores, from 1986 to 1995. After Stern’s, he assumed the position of director of visual merchandising for WalkerGroup/CNI, an architectural design firm in New York City. Feigenbaum was also an adjunct professor of Store Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology and formerly served as the chair of the Visual Merchandising Department at LIM College (New York) from 2000 to 2015. In addition to being the New York Editor of VMSD magazine, Eric is also a founding member of PAVE (A Partnership for Planning and Visual Education). Currently, he is also president and director of creative services for his own retail design company, Embrace Design.

SPONSORED HEADLINE

7 design trends to drive customer behavior in 2024

In-store marketing and design trends to watch in 2024 (+how to execute them!). Learn More.

You may like

Majority of Businesses Still Rely on Cash Payments: Survey

2024 Designer Dozen: Olga Sapunkova

Mango Adding Stores in Washington, D.C., and Boston

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from VMSD magazine's news bulletins.

Most Popular

-

Photo Gallery1 week ago

Photo Gallery1 week agoThe 2024 Shop! Design Awards Winners

-

Headlines4 days ago

Headlines4 days agoTarget Sued for Biometric Surveillance

-

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines1 week agoALDI Launches Checkout-Free Grocery

-

Headlines2 weeks ago

Headlines2 weeks agoLong Island Shopping Center Sold for $8M

-

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines1 week agoMicro Grocery Store Being Built in Tulsa

-

Designer Dozen1 week ago

Designer Dozen1 week ago2024 Designer Dozen: Lisa Rachielles

-

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines1 week agoAnthropologie’s Terrain Unit Opens Store at Brooklyn Botanic Garden

-

Headlines1 week ago

Headlines1 week agoNew Report Reveals How Deeply Retailers Are Affected by Theft